I’ve written previously about the new golden age of SFF adaptations and what, in my opinion, makes them work. Now I’m going to delve into my personal wish list of Things I Want: five(ish) adaptations I wish existed, the forms they should take, and why I think they’d be awesome.

Let’s get to it, shall we?

Anne McCaffrey’s Pern series

I’m not going to preface this choice with an explanation of what Pern is or who the characters are: it’s been around for long enough now–since 1967, in fact–that I’m going to assume a base degree of familiarity. That being so, it doesn’t seem unfair to say that Pern’s great strength is the worldbuilding: Threadfall, Impression, dragonriders, flying Between, the holder system, telepathy, timing it, Harper Halls, firelizards, queen eggs, and the many attendant possibilities thereof. Which isn’t to slight the characters, per se—it has, after all, been many years since I first fell in love with Lessa, F’lar, F’nor, Brekke, Mirrim, Menolly, Piemur and Master Robinton—but, well. Okay. There’s no delicate way to put this, so I’m just going to come right out with it: McCaffrey is weird about sex, where weird is a synonym for rapey and homophobic. Male green riders are frequently denigrated in text, dragon mating is used as a convenient way to handwave consent between riders, and while the conceit of Pern as a society that’s simultaneously feudal and futuristic is a compelling one, the in-text misogyny hasn’t aged well. It’s not just that the setting is sexist, but that the narrative is only sometimes critical of this fact, and if you reread the early books in particular, the consequences of this are… not great (F’lar admitting to raping Lessa, Kylara’s domestic abuse being narratively excused because of her meanness to Brekke, and the female exceptionalism of Mirrim and Menolly being Not Like Other Girls, for instance).

But despite these flaws, the series retains a perennial attraction. Pern is what I think of as a sandbox world: one whose primary draw is the setting, the potential of its environment to contain not just one story and one set of characters, but many. Star Wars is much the same, which is why it succeeds so well across so many different mediums: as much as we love its various protagonists, we’re also happy to explore their world without them, and to make new friends in the process. That being so, it’s impossible for me to imagine just one Pern adaptation: there’s too much going on to want to narrow it down. Here, then, are my top three options:

- A Bioware-style RPG based around fighting Thread. The concept of Impressing a dragon, with all the different colour and gender combinations available, is perfectly suited to giving a custom character different narrative options, regardless of whether who you Impressed was decided by a random dice-roll, your resting place on a sliding scale determined by prior in-game actions, or a simple player’s choice. As in Dragon Age: Origins, players could choose from a series of backgrounds with alternate entry points into the same story depending on whether their protagonist comes from Hall, Hold or Weyr. The overarching plot could centre on a mix of Hold/Hall politics and the search for ancient technological artefacts, with bonus sidequests about running various missions, recruiting potential riders, Harper Hall spying and collecting/apportioning fire lizard eggs. Dragon powers like timing it and going Between could work as in-game combat abilities, while romance options could be intertwined with—though not wholly dependent on—dragon pairings. (And nor would such options be exclusively straight: however poorly handled in the source material, the presence of male green riders confirms that Impression isn’t reflective of sexual preference, and that dragons can be Impressed by riders of different genders. Remove the patriarchal impetus of the setting, which is the real reason girls were only ever selected as potential gold riders—Mirrim, after all, quite handily Impressed a green—and I see no reason why, even if queen dragons were retained as female-only, you couldn’t have girls riding blues, browns and bronzes, too. Basically, GIVE ME ALL THE QUEER DRAGONRIDER OPTIONS, because why the hell not?)

- A TV series based around Harper Hall spying and politicking, following the exploits of Menolly, Sebel, and Piemur. The dragons are such a big, shiny, visible part of Pern that it’s easy to miss the narrative potential of everything that sneaks along in the background, even when it’s politically meatier. Given that the Harpers are at the centre of historical and social progress, they’re the perfect lens for a long-game look at Pern—plus, I’m guessing that fire lizards would be easier to animate week-to-week than full-size dragons.

- A movie about Lessa: her Impression of Ramoth, her inheritance of the broken, depleted Weyrs at the end of a long Interval, her puzzling out of clues about Threadfall and her leap back in time to bring the Oldtimers forward. It’s the perfect arc for a film, tightly plotted around a single main character whose trajectory natively serves as a worldbuilding mechanism, with exactly the kind of big-budget visuals—dragons! aerial battles! Thread!—that work best as cinematic spectacle.

Any one of these projects would bring endless delight to my fannish heart; all three together would probably cause me to expire from a surfeit of pure joy.

Court of Fives, by Kate Elliott

It’s no secret I’m a longtime fan of Elliott’s work—which is endlessly compelling, diverse and imaginative—but of everything she’s written so far, it’s her first foray into YA, Court of Fives, that strikes me as being perfect for film. Set in a Greco-Egyptian setting, the plot revolves around the game of Fives, an incredibly well-developed sport whose competitors have to run a series of mazes against each other in order to win, with each section requiring a different combination of strength, tactics and agility for successful completion. The protagonist, Jes, is a young biracial woman of noble birth who competes in secret, defying what’s expected of girls of her background. When her decision to run the Fives dovetails with her father being politically outmanoeuvred, their whole family is endangered—and only Jes has the freedom to try and save them.

As a concept, the Fives scenes would look fantastic, as well as providing a solid, engaging structure around which to hang the story. The climax is equally tense and well-written: the sort of storytelling that takes chapters to describe on page, but which looks effortless on screen. The worldbuilding, too, has a strong visual component in everything from clothes to architecture—I’d love to see Elliott’s world brought to life, and given the clear historical inspiration, it’s the perfect mix of familiar and original elements to show that a bigger setting exists without overburdening the dialogue. The diversity of the characters is another point in the story’s favour: not only is race a narratively relevant issue, but as Court of Fives is a secondary world fantasy, it’s one that allows a lot of scope for casting interpretation. (Meaning: it’s very hard to say ‘but REAL Greeks don’t look like that!’ when the whole point is that these are not, in point of fact, “real” Greeks.)

Court of Fives has all the best elements of the most successful YA film adaptations—an original, three-dimensional protagonist struggling to navigate both gladiatorial and political arenas (the two being fundamentally connected), complex family relations, a decent romance, and an action-packed plot which, as firmly as it leaps off the page, would look brilliant on the big screen. SOMEBODY PURCHASE THE RIGHTS AND ADAPT IT IMMEDIATELY.

Seanan McGuire’s October Daye series

To say that Seanan McGuire is a prolific writer is an understatement akin to calling the sun warm: it’s technically accurate, but absent a vital degree of HOLY SHIT intensity. Rosemary and Rue, McGuire’s first published novel and the start of the October Daye series, came out in 2008; counting her slated releases for 2016, she has, since then, produced twenty-seven novels and short story collections, to say nothing of her myriad novellas and short stories, which is more than most authors manage in a lifetime. That many of her shorter works are set in the same universe(s) as her various novels is a testament to the breadth of her worldbuilding: no matter how action-focused McGuire’s stories become, there’s always a wealth of magic, mad science and originality underlying everything that happens. [Editor’s note: since the original publication of this article, the October Daye series has grown to include 15 novels, with a 16th forthcoming in September 2022.]

At the start of the series, October ‘Toby’ Daye is a changeling: a half-human detective and former faerie knight working cases that cross into San Francisco’s Faerie realms. It’s urban fantasy, noir and Childe Rowland all rolled together with a heaping of snark and geek references, and in the right hands, it would make for an incredible, addictive TV show. If the novels have a weakness, it’s that there’s so much going on in parallel in McGuire’s world—much of it hinted at early on, but not addressed until later books—that Toby’s first-person perspective simply can’t show us everything at once. But in a TV format, all that juicy worldbuilding and backstory detail could be given more space, the secondary characters portrayed through eyes other than Toby’s. This is a character, after all, who spends fourteen years trapped as a koi fish in the Japanese gardens before the story even starts, returning home to find the various parts of her life either broken, destroyed or fundamentally altered in her absence.

Give me an October Daye series (preferably starring Crystal Reed as Toby, please and thank you, she would be LITERALLY PERFECT, FIGHT ME) which folds the events of multiple books into each season, creating a layered narrative that knows its own long game from the outset. Give me a racially, sexually diverse cast of faeries roaming the streets of San Francisco with a wry, Noir-style narration and plenty of explosions. YOU KNOW YOU WANT TO.

Archivist Wasp, by Nicole Kornher-Stace

The trick to making movie adaptations of SFF novels is to pick a story which shortens rather than lengthens in the transition to screen, thereby giving the filmmaker some leeway to interpret the plot without stripping it. Prose has a different set of strengths and weaknesses to film, and vice versa: an action sequence that takes fifteen pages to describe might be visually conveyed in two minutes, while a subtle piece of background information, worked seamlessly into written narration, might require an extra half hour in order to make sense on film. This is, I would argue, the most practical reason why demanding pristine, page-to-screen adaptations is a bad idea: unless your source material is an especially well-constructed comic or graphic novel, the fundamental differences between the mediums means the story has to change, or suffer in the retelling.

Which is, perhaps, why it’s often shorter works of SFF—be they YA or otherwise—that make the strongest films: the scripting doesn’t have to rush to cram things in, or risk incompleteness for the sake of brevity. Archivist Wasp is the perfect length for film, and premised on the sort of compelling, dystopian uncertainty about what’s happening now and why things broke that worked for All You Need is Kill (filmed as Edge of Tomorrow/Live. Die. Repeat.) and I Am Legend. In fact, you could arguably pitch it as a blend of the best elements of those two stories, with just a pinch of (seemingly) magic. In a harsh, barren future, Wasp is forced to capture ghosts to try and question them about what happened to the world—a largely futile task, as most ghosts are incoherent. But when one ghost proves stronger, fiercer, and more lucid than the others, going so far as to ask Wasp’s help in finding his companion, Wasp follows him out of her body and into the world of dead. Aided by her access to his disintegrating memories of what happened before—flashbacks of an unknown time that steadily lead them onwards—Wasp comes to question everything she’s ever been taught about the world that remains and her bloody, brutal place within it.

My only complaint about Archivist Wasp, an entirely excellent book, is a matter of personal preference: given the dystopian setting and high technological past, it’s simply never explained how the death-magic element fits into things. On page, it reads to me as a Because Reasons elision, but lack of an explanation, while personally irksome, doesn’t change the coherence or emotional impact of the story otherwise. More saliently in this instance, it’s exactly the kind of element we tend not to question when present on screen: there used to be skyscrapers, and now there are ghosts, and it doesn’t really matter how or why, or if the ghosts were always there—the point is the inwards journey, reflective of external transformation, and what it means for the characters.

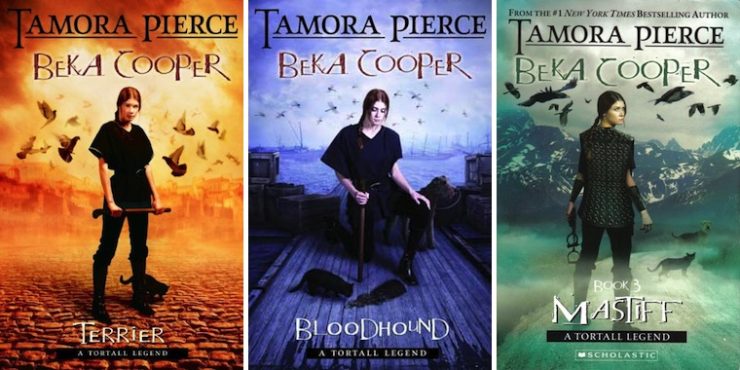

The Beka Cooper trilogy, by Tamora Pierce

As long as Tamora Pierce has been around, and as utterly beloved as her works are, I honestly can’t understand why no one has ever tried to adapt them before. Forced to pick just one of her series to talk about, I’m very nearly tempted to err on the side of Emelan and the Winding Circle quartet, but as much as I love Briar, Sandry, Tris and Daja, the trickiness there is the age of the characters: they’re all eleven or so at the outset, and while you can get away with middle grade novels that unflinchingly deal, as Pierce’s work does, with prejudice and violence, bringing them to screen in all that graphicness is much, much harder. Harry Potter is an exception and a yardstick both, but for the sake of comparison, imagine if the worst events of the later books were happening to the early, prepubescent versions of the characters, instead of being the result of several years of steady escalation, and you’ll get a sense of the obstacle.

The Beka Cooper books, however, are a different matter. Though the subject matter is just as thematically dark, the protagonist is that crucial handful of years older, and frankly, the idea of a feudal police drama with magic, with each season built around the events of a given book, is appealing as hell. There’s a reason urban fantasy adapts so well to TV, when the people in charge understand its peculiarities: the procedural elements translate well to an episodic format, while the worldbuilding provides extra narrative avenues as the story progresses, and used together, the two things pull in harmony. Beka is one of my favourite Pierce protagonists: a trainee guard from a poor background who initially finds herself on the trail of a child-killer, her persistence and resilience set her apart, both narratively and among her peers. (And as a secondary-world fantasy which deals, among other pertinent issues, with abuse of power, poverty, slavery and police brutality, it’s hard not to think that such a series, were it produced now, would find strong thematic resonance in current events.)

* * *

The one thing that irritates me about this list is its whiteness (of creators, not characters). I count this a personal failing: thanks to depression of varying kinds, I’ve struggled to read in the past two years, which means I’ve stalled out on a lot of excellent books, and as there are fewer POC-authored works being published in the first place, my reading of POC authors has been disproportionately affected by it. On the basis of what I’ve read of them so far, however—and glancing at the very top of my TBR pile—I suspect that, were I to write a future, supplemental version of this column, Zen Cho’s Sorcerer to the Crown, Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Signal to Noise, Daniel Jose Older’s Half-Resurrection Blues, Aliette de Bodard’s The House of Shattered Wings and Malinda Lo’s Adaptation would feature prominently: all have elements that spark that same sense of visual excitement for me, and that I’m still getting through them is reflective of my own failings, not theirs.

Which isn’t to say I haven’t read any excellent works by POC recently; quite the contrary. (I’m specifying recently, because most of what I read growing up, before I gave the matter any conscious thought, was by white authors.) It’s just that, for whatever reason, the ones I have finished haven’t struck me as being easily adaptable. To give the most obvious example: even had the ending of Kai Ashante Wilson’s Sorcerer of the Wildeeps not viscerally upset me, its strength lies in its otherwise sublime, intelligent contrast of internal and external dialogue, expressed through the narrator’s varying degrees of fluency with different languages—a trick of linguistic worldbuilding which, while stunning in prose, is excruciatingly difficult to replicate on screen. On the page, we’re effectively seeing multiple fictitious languages ‘translated’ to English, the different degrees of Demane’s facility with them reflected in Wilson’s use of different types of English. But on screen, where the characters would need to be shown to be actually speaking different languages, that comparison would, somewhat paradoxically, be lost in the act of making it real: not only would we lose Demane’s internality, but we’d miss the impact of having the fictitious languages be identically interpretable to the audience while remaining at variance to the characters.

All of which is a way of saying: in thinking about the stories I most want to see adapted, I’m not barracking for my favourite series of all time (or we’d be looking at a very different list), but specifically for narratives which, I think, would thrive in the act of adaptation—stories which wouldn’t lose their most fundamental aspect in transitioning between mediums, but which can either take that strength with them, or find it there anew.

That being so, which SFF works would you most like to see adapted, and why?

Buy the Book

A Strange and Stubborn Endurance

Originally published in February 2016.

Foz Meadows is a queer Australian author, essayist, reviewer and poet. She has won two Best Fan Writer awards (a Hugo Award in 2019 and a Ditmar Award in 2017) for yelling on the internet, and has also received the Norma K. Hemming Award in 2018 for her queer Shakespearean novella, Coral Bones. Her essays, reviews, poetry and short fiction have appeared in various venues, including Uncanny, Apex Magazine, Goblin Fruit, HuffPost, and Strange Horizons. Meadows currently lives in California with her family. A Strange and Stubborn Endurance is her fifth novel.

Piper’s TFH seems very adaptable now that cgi is up to Ullerans and Fuzzies. Four Day Planet would have some interesting resonances these days

I have thought before that Diane Duane’s So You Want To Be A Wizard (the first in the Young Wizard series) could make for an excellent screen adaptation. Back in 2012, there were plans afoot for just such an adaptation, and Duane even posted a couple of snippets of screenplay online, but it seems that those plans did not pan out.

Bujold!!!!

I also strongly agree with the Kate Elliot pick. Fun series.

Ditto re October Daye but that would be an ambitious undertaking, given the size and scope of the world. (I could just imagine the Season 2 or Season 3 opening with October’s Fetch showing up at the front door.)

Agree with #3 Rob, Bujold’s Vorkosigan series in particular has great world building, awesome stories, and great characters including great female characters. This would be a great playground for movie makers

For POC possibilities: Moreno-Garcia’s Gods of Jade and Shadow would be a great mini-series, one episode per major obstacle; might or might not fit into one movie. (I don’t remember enough of Signal to Noise to guess whether it would work.) Also, Tracy Deonn’s Legendborn seems like it would work as a miniseries — with possible additional series, as there’s at least one more book coming.

For older possibilities: I’ve been wanting a movie of Merchanter’s Luck ever since first reading it; it’s compact enough to fit in one movie and has plenty of drama (in terms of finding solutions under strain rather than Gordianizing them with combat) and an ending that Hollywood should be drooling over.

wrt McCaffrey’s treatment of Green riders: notice how old these books are; I remember her (in 1975) telling how delighted she was when a reader was shocked to realize that much of a weyr was gay. (Memory is unclear whether Green riders are the only ones looked down on — ISTR a hierarchy of size of mount, such that Blue riders were also looked down on, and there was even question whether a Brown rider could lead. This might also need fixing.) I take as a sign of progress that what was a step forward at the time is now insufficient, although I wonder how many studios would be willing to acknowledge what McCaffrey set up rather than trying to hide it.

I want the creators of Avatar: The Last Air-Bender to adapt the Cradle series by Will Wight.

The Lockwood & Co. series by Jonathan Stroud could be a good series of movies.

I am there for a Harper Hall series.

Ed.: “Kyala” s.b. “Kylara”; “Miriam” s.b. “Mirrim” throughout; my autocorrect should stay at its desk until asked for (okay, that last one is a me problem).

@8 – Fixed, thanks!

Andre Norton’s “Witch World” series could make a great TV series as well.

I would LOVE to see a Pern adaptation where Ramoth’s rider goes to the dark side and does more than one bad deed.

You could call it “The Lessa of Two Evils”

(sorry folks it’s been a looonnng week)

I’d like to see Jim Butcher’s “Dresden Files” given a better adaption than that TV series although I loved Paul Blackthorne as Harry. I’ve heard rumors that this might happen.

Steven Erickson Tales of Bauchelian and Korbal Broach.

I totally back the Lessa movie, and would also vote for Bujold adaptations. @2, I also regret that the movie of So You Want to Be a Wizard failed to materialize. But then, the movie adaptation of Vonda McIntyre’s The Moon and the Sun never *should* have materialized….

In other mermaids…I think Bethany Morrow’s A Song below Water would make a fine movie, with clear social relevance. If they do it right, it could be the best movie out there addressing BLM protests.

And the book I read thinking, “This is a natural for movie adaptation” is Daniel José Older’s Shadowshaper. The book is the first of a trilogy, but it stands alone well and would do so on screen. I want to see those murals come alive!! Like Morrow’s book, this one has authentic representation, diversity, social justice issues, all integral to the narrative flow.

Given the present situation I think the time is ripe for an adaptation of David Gemmell’s “Waylander”. The sometimes bleak depiction of invasion, occupation, atrocity and resistance would be timely.

I ‘d love to see Paris of the House if Shattered Wings on the screen…

Book of the New Sun by Gene Wolfe. It’s got everything – an orphaned little boy – raised by the Torturer’s Guild. Grave robbers. True love. Betrayal. A humongous sword. The color darker than black. A jewel heist. A duel. Calvary battles. A story competition and a play performance that were perhaps inserted when the publisher wanted the planned trilogy converted to a quartet. A cute three-legged dog. The raising of the dead. Aliens from outer space! Ritual cannibalism. A powerful talisman! Attacks by air and earth and fire and water. A giant. A mad scientist.

@17: It would work better in musical theater, under the title You Say Al-Zay-Bo, I Say Al-Zah-Bo.

How about Zelazny’s The Chronicles of Amber books – it can be pitched as Succession with magic.

1. The Stainless Steel Rat books by Harry Harrison.

2. The ‘Hunter Kiss’ novels by Marjorie M Liu

3. The Crystal Singer trilogy by Anne McCaffrey

4. The Kate Daniels books by Ilona Andrews

5. Anything written by Robin Hobb

@@@@@#6 The problem with green riders is not that they are gay, but their dragons *turn them gay*.

There are so many layers of misogyny, homophobia and sexual violence in Pern I can’t get behind an adaptation. Even an adaptation that cleaned that up would bring up so much dreck for fans and the estate that I feel like it’s just not appropriate. Maybe in some future decade when the issues are quaint relics of the past.

The books Ambassador and Nomad by William Alexander. Great universe, great characters and plot. There are hints of Have Space Suit, Will Travel with the kid as representative of Earth, but this is a lot better.

Novellas are a nice match to movie length. Aliette de Bodard’s Xuya works could make great film.

The first time I read The Martian Way, I thought it should be a movie.

Seanan’s “Parasitology” trilogy would adapt well. Not too much difficult cgi to worry about.

The only downside to a Vorkosigan adaptation is that we waited too long and Peter Dinklage has aged out of the possibility of playing Miles, darn it.

I’d love to see some of Ursula Vernon’s stuff adapted. Turn Studio Laika loose on Castle Hangnail, convince the Jim Henson company to give Digger another look, give me a Seventh Bride miniseries!

Monument by Lloyd Biggle Jr – A movie or a 1 season mini-series

The High Crusade – Poul Anderson – This was made into a low budget movie, time to reboot

The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress & Glory Road – I’d like to see these given the mini-series treatment. There’s enough meat that one movie would be rushed.

Ancillary Justice – Anne Leckie

Ben Aaronovitch’s Rivers of London series is crying out to be a TV series (and Aaronovitch is also a TV writer, so he could even be involved in the adaptation).

This would probably run into problems at the moment given that the main character is a DC with the Metropolitan Police and the Met are currently… not wildly popular, especially with women… plus TV producers in the UK are trying to move away from a London focus, but maybe in a few years?

@25 Ancillary Justice is getting adapted! Keira Knightley has already been cast (as mentioned here), which I’m not sure about because IIRC all of the characters were supposed to be brown, but I’m still hopeful.

Seeing what the Industry has done to A Song of Ice and Fire; Wheel of Time and Rings of Power, not to mention The Watch! the last thing I want is for them to go after another beloved series!

I’ll second (third?) a movie adaptation of So You Want to Be a Wizard and jump on the Vorkosigan/Bujold bandwagon. I think Witch Week by Diana Wynne Jones would make a good stand-alone movie, even if it is part of the Chronicles of Chrestomanci. And I would love to see an adaptation of Naomi Kritzer’s Catfishing on CatNet. (There are ways to bring those AI monologue scenes to life with a bit of animation and/or CGI, and you could change the text-chat conversations to voice-chat scenes.)

Don’t apologize for liking white people!

I love Europe, European culture, and European stories, and not ashamed at all :)

“The Velocity of Revolution” by Marshall Ryan Maresca. It would have to be as a miniseries or series though, the world is so rich, I would hate to miss any of it. Telepathy, motorcycle races, economic, national, racial issues present and part of the plot. Yet inspiring and beautiful, with a rapid and compelling plot. The only problem I had was that the descriptions of the varieties of taco the characters ate (a lot!) was so mouthwatering, and SoCal or Mexico so very far away.

I also recommend Midnight Robber and/or Sister Moon by Nalo Hopkinson, which are short enough for movies, cool enough locations that are earth-adjacent enough not to need too much CGI. Not so weird as to have a narrow audience, not the same old medieval-Europe setting. Also the Jade City books by Fonda Lee. Magic, martial arts, and mafia (ish). The combination of invisible magic-aided visual martial arts would be tricky, but I think it could be as simple as having the character voice-over the name of the invisible part. Or visually with call-outs, as they do to show texting visually. OK back to lurking.

@24: oooh, yes, Studio Laika doing Castle Hangnail, yes please!

Rendezvous with Rama – just the original book; single season miniseries; plenty of “sensawundah,” a relativistic universe, and a fairly “positive” story, in general.

Poul Anderson’s Technic Civilization series – enough material for a combined Star Trek/Star Wars/Marvel-verse; start with a Flandry “Bond in Space” mini-series and if it takes off, work back and forth, from Anderson’s late 21st Century Solar System onwards and outwards.

– The Pendragon series (D.J. MacHale): a multi-season miniseries, similar to Alex Rider or His Dark Materials

– The Raven Cycle (Maggie Stiefvater): a multi-part video game in the same style as Life is Strange

– The Leviathan series (Scott Westerfeld): an animated series, similar to Avatar: The Last Airbender/The Legend of Korra

– Snow Crash (Neal Stephenson): an open-world narrative-driven action/mystery rpg kinetic parkour-infused video game, like a mix between Mirror’s Edge, Disco Elysium, Need for Speed, Control, and Half-Life

– To Say Nothing of the Dog (Connie Willis): a narrative-driven mystery video game farce, like a mix of Life is Strange and Untitled Goose Game

– The Last Dragon Chronicle (Chris D’Lacey): anything; I just want to know just how bizarre any adaptation of this book series would end up being

– The King Raven Trilogy (Stephen R. Lawhead): a 4+ -hour-long Kenneth Brannagh Shakespearean film adaptation

– From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler (E.L. Koenigsburg): a made-for-TV kids movie

– The Broken Earth Trilogy (N.K. Jemisin): stageplay adaptation

– The Last Truth (AnaMaria Curtis): film or short film, that focuses on evoking the main character’s mental/emotional experience, similar to Arrival or It’s Such a Beautiful Day; alternatively: a short anime series, film, or a video game that can similarly evoke the main character’s experience with memory in an intimate/personal way

@30

they didn’t. They correctly objected to whitewashing a lead role by casting a white actor in a role specified as non-white in the source material. You know, just like the adaptations of Earthsea did. And Breq isn’t European; she started out as AI.

Sticking with Kate Elliot, I’d be interested to see an adaptation of The Golden Key. Such a well developed world.

Murderbot Diaries as a short series or TV show, I personally would prefer love action. I think it w

Bester’s The Stars My Destination is a cinematic read, I’ve wanted to see a miniseries of it for years.

Some time ago, I heard that Peter Jackson had optioned Naomi Novik’s Termeraire series. But who knows?

Anything from Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle. There’s been talks to adapt both The Dispossessed and Left Hand of Darkness for years now, all the way back in 2017 for the latter. I’d love to see these two books adapted into a limited or even one-two season series, but given how very left-leaning they are, I doubt any big studio would pick them up much less create an adaptation that gives them justice. I’d still love to see an anthology series like Love, Death, and Robots for her short stories.

I think Jerry Pournelle’s King David’s Spaceship might be fun, star ships, cavalry, pirates and a barbarian horde all in one novel. Set in the same universe as The Mote in God’s Eye.

I’d like a very beautiful, very carefully made film trilogy adaptation of Patricia A McKillip’s Riddle-Master trilogy – but gosh, you’d have to be very precise about who you cast as Deth…

Give us Temeraire! Peter Jackson bought the rights and then did nothing . . . 8-(

@26 I had heard Nick Frost and Simon Pegg were behind a ‘Rivers of London’ adaptation.

Mistborn – still waiting for rights to go somewhere.

Strongly second the shoutout to Robin Hobb

Murderbot would be amazing, as would Ancillary Justice.

I’d really love to see some Vlad Taltos on screen as well….Ditto for Cherryh’s Foreigner series, but that truly might be unfilmable.

@21: I don’t remember that from the early books; I may have failed a memory check, or that may have been explicit only in books after I gave up in Pern because the writing, plotting, … had gone south.

@24: All (that we are shown) of Miles is short, not just the legs. See, e.g., the NESFA edition of The Warrior’s Apprentice (cover approved by Bujold). His parts of the stories might be done by the same kind of optical tricks as were used in The Lord of the Rings, or there might be better tech now.

Jack Vance Cugel.

*sigh* No one ever mentions Lynn Flewelling’s Nightrunners series. Seregil and Alec and Micum, such a sweet found family.

Definitely the Vorkosigan Saga. I’d also love to see the Stormlight Archive onscreen, preferably as a TV show with theater release quality effects. And can I please have a complete movie series of the Chronicles of Narnia finally? I desperately want to see my favorite girl, Aravis, doing spontaneous espionage and for Hwin to finally get a chance to shine.

Gaunts Ghosts

Cook’s “The Black Company” series.

Kay’s “The Fionavar Tapestry”.

Vance’s “Lyonesse” trilogy.

The Worm Ouroborous

Lord of Light

Harold Shea Compleat Enchanter stories (multi-season show)

Rod Gallowglass Warlock In Spite of Himself stories (also multi-season)

@53 judging by the recent adaptations of WoT and GoT, can we even remotely hope they would do The Worm Ouroborous remote justice though? That is one amazing book and I’m not sure I’d want to see it get mangled like the others…

I’d love to see The Lunar Chronicles by Marissa Meyer as a four-season TV series and Blackout/All Clear by Connie Willis as a miniseries.

And I agree with 49 that it’s past time we got to see Aravis and Hwin on the big screen! (Gosh, at this point, the actors who played the Penvensies in the trilogy could play themselves in this movie.)